NEWS

Tuesday 4 August 2020

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are still being felt the world over, but we’re already aware that not everyone has been impacted equally. What has become clear from the vast amounts of published data is that gender, race and wealth all play a significant part in how COVID-19 will affect someone, whether from a health, economic or social perspective.

Men, for example, are at greater risk of contracting and dying from COVID-19 than women, whereas women are more likely to suffer financially. In Mexico, the ratio of those dying from COVID-19 is as much as 66% men versus 34% for women, the highest gender differentiation of any country with over 10,000 deaths.1 As the World Bank points out, “evidence shows that coronavirus is deadlier for men; however, women are facing more economic hardship.”2

Evidence suggests that in Western economies, those from Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) communities seem to be at greater risk of contracting and dying from COVID-19 than those from white ethnic groups. According to research published in the Financial Times, while people of BAME origin make up about 13% of the UK population they account for around a third of virus patients admitted to critical care units. In the US, Black Americans represent around 14% of the population but 30% of those who have contracted the virus.3

Wealth also appears to have a significant impact on whether someone is likely to contract COVID-19. While the virus does not discriminate based on actual bank balance; whether someone lives in crowded conditions, has access to healthcare, or works in a safe environment are all factors significantly impacted by a person’s wealth and, unfortunately, all increase the risk of catching a contagious disease.

…gender, race and wealth all play a significant part in how COVID-19 will affect someone, whether from a health, economic or social perspective.

Is gender equality going backwards?

Evidence also suggests that inequalities in the balance of labour and the impact of gender stereotyping have been made worse during lockdown. According to the United Nations, women carry out at least two and a half times more unpaid household and care work than men.4 Women in India carry out ten times more unpaid housework and social care during ‘normal’ times than men, and COVID-19 is estimated to have increased this by a further 30%.5

And according to data from the International Labour Organisation, across the world women represent less than 40% of employment but make up 57% of part time work.6 This often means work is more temporary, or unstable, than a full-time position. There remains a significant gender pay gap too, currently stuck at 16% globally, which means women will be disproportionately affected by an economic downtown.7

Even when women can work from home, they tend to take on a greater proportion of the childcare and household chores, which will limit their ability to be able to work full time hours, especially now that home schooling, albeit temporary, has become commonplace .

According to the United Nations Policy Brief: “Across the globe, women earn less, save less, hold less secure jobs, are more likely to be employed in the informal sector. They have less access to social protections and are the majority of single-parent households. Their capacity to absorb economic shocks is therefore less than that of men.”8

Across the globe, women earn less, save less, hold less secure jobs, are more likely to be employed in the informal sector…. Their capacity to absorb economic shocks is therefore less than that of men.

The impact of policy

The impact of policy

Decisions have been made that affect the way of life for pretty much everyone across the globe but the impact of those decisions by policy makers and health officials is not necessarily the same for men and women.

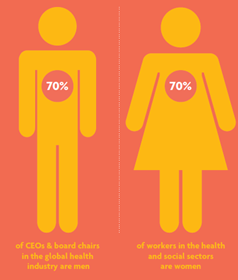

Analysis of 104 countries by the International Growth Centre shows around 70% of workers in the health and social sectors are women, while over 70% of CEOs and board chairs in the global health industry are men, suggesting that while many women are working on the COVID-19 frontlines, very few are able to influence the policy measures in place to deal with the crisis.9

Does the virus discriminate?

If one thing is clear about COVID-19, it is that it’s incredibly contagious and spreads without discrimination. But a person’s ethnicity does seem to play a part in the likely health impact. Analysis by the Institute of Fiscal Studies shows that the death rate among British Black Africans and British Pakistanis from COVID-19 in English hospitals is more than two and a half times that of the white population.10 And a report by the British Medical Association found 90% of doctors who had died from COVID-19 were from a BAME background.11

In the UK12, data suggests people of South Asian origin are the group most likely to die in hospital of COVID-19. There are a few reasons for this but it seems likely to be linked to diabetes, a known significant pre-existing condition which has a direct impact on COVID-19 morbidity. About 40% of South Asian patients in hospital had either type 1 or type 2 diabetes, compared with 25% of white patients.

[COVID-19 is] incredibly contagious and spreads without discrimination. But a person’s ethnicity does seem to play a part in the health impact.

It is, however, difficult to get a clear picture of how the virus is affecting those living in South Asian countries. For example, it has been widely reported that India (as with a number of other countries) may be underreporting the number of people who have died from COVID-19. Doctors in some regions report being instructed not to list COVID-19 as the cause of death in patients with the virus. And while India’s healthcare system allows everyone to receive either free or highly subsidised care at public hospitals, it has also been chronically underfunded. World Health Organization (WHO) data shows that India’s government spent just $63 per person on healthcare for its 1.3 billion people in 2016 while China spent $398 for each of its 1.4 billion people.13

It is, however, difficult to get a clear picture of how the virus is affecting those living in South Asian countries. For example, it has been widely reported that India (as with a number of other countries) may be underreporting the number of people who have died from COVID-19. Doctors in some regions report being instructed not to list COVID-19 as the cause of death in patients with the virus. And while India’s healthcare system allows everyone to receive either free or highly subsidised care at public hospitals, it has also been chronically underfunded. World Health Organization (WHO) data shows that India’s government spent just $63 per person on healthcare for its 1.3 billion people in 2016 while China spent $398 for each of its 1.4 billion people.13

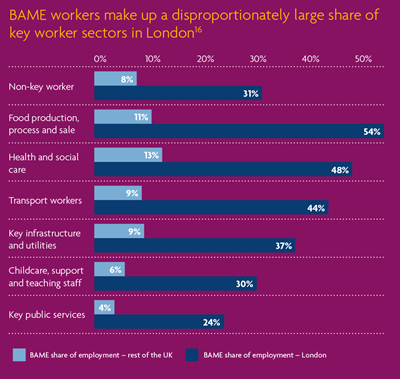

In countries with a majority white population, one reason ethnic minorities may be at greater risk is due to living conditions, as minority communities are often more likely to live in multi-generational households, with extended families mingling in more crowded conditions.14 Another reason may be due to the likelihood of holding a key worker position. About 8% of the UK workforce are key workers but this rises to 31% of those from a BAME background.15 BAME workers make up 54% of London transport workers, 48% of health and social care workers and 54% of food production and processing workers – an environment where there’s been a high number of reported cases of COVID-19 across the world.

Ross Warwick, research economist at the Institute for Fiscal Studies, said death rates among minority populations could be down to underlying health or job roles. “When you account for the fact that most minority groups are relatively young overall, the number of deaths looks disproportionate in most ethnic minority groups. There is unlikely to be a single explanation here and different factors may be more important for different groups. For instance, while Black Africans are particularly likely to be employed in key worker roles which might put them at risk, older Bangladeshis appear vulnerable on the basis of underlying health conditions.”

About 8% of the UK workforce are key workers but this rises to 31% of those from a BAME background.

Hospitalisation rates and characteristics of patients hospitalised with COVID-19 in the US

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC)17 recently conducted analysis among 580 patients hospitalised with lab-confirmed COVID-19 in 14 US States. The study found that 45% of individuals for whom race, or ethnicity data was available were white, compared to 59% of individuals in the surrounding community.

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC)17 recently conducted analysis among 580 patients hospitalised with lab-confirmed COVID-19 in 14 US States. The study found that 45% of individuals for whom race, or ethnicity data was available were white, compared to 59% of individuals in the surrounding community.

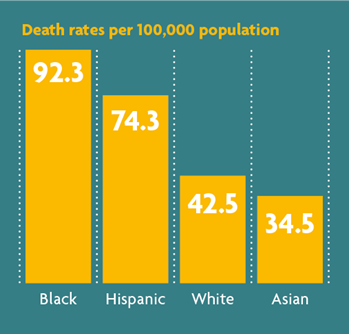

However, 33% of hospitalised patients were black, compared to 18% in the community, suggesting an overrepresentation of Black people among hospitalised patients. New York City18 identified death rates among Black (92.3 deaths per 100,000 population) and Hispanic people (74.3 deaths per 100,000) that were substantially higher than that of White (42.5 per 100,000) or Asian (34.5 per 100,000) persons.

Can you buy your way out of infection?

While COVID-19 can’t tell if someone is rich or poor, infection rates do seem to be impacted by economic status. Prior to this pandemic, research found that a low income relative to the rest of society is associated with higher rates of chronic health conditions like diabetes and heart disease,19 both of which severely increase the risk of death from COVID-19. At the same time, studies have shown that those with lower incomes tend to develop chronic health conditions between five and 15 years earlier in life.20 While health officials believe those over 70 are most at risk due to the prevalence of chronic conditions, these findings suggest that for people on lower incomes, it is likely that the threshold may be as low as age 55.

The wealth inequality is likely to be felt more in countries which don’t offer state funded healthcare. In the US, for example, 90% of people whose income is in the top quarter have paid sick leave at work, while only 47% of those in the bottom quarter do.21 In 2019, 26% of Americans deferred healthcare22 because they could not afford it, while a similar proportion said someone in their family had missed a doctor-recommended test they could not afford.23 It’s a fair assumption that cost of treatment for some will be unaffordable. A New York Times article suggests many face unpleasant hospital bills for treating COVID-19, with some even charged for mandatory stays.24

As we have seen, lower paid jobs are often those performed on the front line during a pandemic, with health care staff, transport workers and food production workers paid lower than average wages in many countries. Not only does this put them at greater risk of contracting the virus than wealthier people, it also means they are less likely to have medical insurance if needed.

As we have seen, lower paid jobs are often those performed on the front line during a pandemic, with health care staff, transport workers and food production workers paid lower than average wages in many countries. Not only does this put them at greater risk of contracting the virus than wealthier people, it also means they are less likely to have medical insurance if needed.

According to data reported by Forbes, “Almost half of nurses and home health care workers in the US don’t have a single day of paid sick leave and a million health care workers lack health care coverage themselves. Nurses and orderlies, including those treating COVID-19 patients are risking their lives every day for an average hourly wage of $14.25, while home health care workers’ hourly wage is just $11.63”.25

....studies have shown that those with lower incomes tend to develop chronic health conditions between five and 15 years earlier in life.

Roles of employers

Global organisations must be flexible in their approach to managing the COVID-19 pandemic among staff. A ‘one size fits all’ approach will not work when the epidemiology is so varied in different countries around the world, although strict hygiene procedures should be universal. As the CDC points out, “employers should respond in a way that takes into account the level of disease transmission in their communities and revise their business response plans as needed.”26

In terms of gender equality especially, employers can have a lasting positive impact in workplace policies. Particularly in developed countries, women often request and prioritise workplace flexibility.

If employers use the pandemic as an opportunity to actively promote home working and flexibility, this could be great news for working women who could find that they have more professional opportunities available to them. But for real and sustained gender equality, men need to be offered the same opportunities for flexible working as women, in order to be able to share childcare and other domestic responsibilities fairly.

According to the United Nations Women Empowerment Principles: “The current situation provides a chance to disrupt gender stereotypes, change traditional narratives, and show that leadership and decision-making, household chores, and caring for and teaching children can and should be shared responsibilities.”27

There is an opportunity for employers to take a leading role in addressing the potential long-term negative impact of COVID-19 on existing inequalities. While not responsible for setting healthcare or housing policy, employers do have a responsibility to their workforce. Global organisations have an obligation to ensure their employees are safe in whatever setting they work in, whether a factory or a head office. Those designing return to work policies will need to keep this in mind, while social distancing is possible in an office, it may not be the same in a manufacturing plant or food processing factory.

While the full impact of the pandemic is yet to be known, as countries start relaxing lockdown rules and opening up to the world, there is a role for global organisations to play in ensuring that those who have suffered the most during COVID-19 are supported as everyone begins to rebuild. As a global employer, you need to be aware of existing inequalities and do what you can to ensure these aren’t made worse during and after the COVID-19 crisis.

1 Anon, Global Health 5050 https://globalhealth5050.org/covid19/sex-disaggregated-data-tracker/ (sourced June 2020)

2 Caroline Freund & Iva Ilieva Hamel, World Bank https://blogs.worldbank.org/psd/covid-hurting-women-economically-governments-have-tools-offset-pain, (sourced June 2020)

3 Clive Cookson & Richard Milne, Financial Times https://www.ft.com/content/5fd6ab18-be4a-48de-b887-8478a391dd72 (29 April 2020)

4 Anon, UN Women https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/csw61/redistribute-unpaid-work, (sourced June 2020)

5 Anon, FSG https://www.fsg.org/sites/default/files/7%20issues%20affecting%20women%20during%20covid-19_0.pdf, (sourced June 2020)

6 Anon, International Labour Organization, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_457317.pdf (sourced June 2020)

7 Anon, UN Global Compact Academy https://unglobalcompact.org/academy/how-business-can-support-women-in-times-of-crisis, (sourced June 2020)

8 Anon, UN Women https://www.unwomen.org/-/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2020/policy-brief-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-women-en.pdf?la=en&vs=1406, (sourced June 2020)

9 Laura Sili, International Growth Centre, https://www.theigc.org/blog/covid-19-and-the-impact-on-women/, (sourced June 2020)

10 Haroon Siddique, The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/01/british-bame-covid-19-death-rate-more-than-twice-that-of-whites (1st May 2020)

11 Anon, BBC News https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-53065306 (16th June 2020)

12 Ewen M Harrison & Annemarie B Docherty, The Lancet, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3618215 (sourced June 2020)

13 Anon, Associated Press, The Hindustan Times https://www.hindustantimes.com/health/covid-19-pandemic-india-s-social-inequalities-reflected-in-coronavirus-care/story-Y5mfBH7zOawp6mwK59d0AP.html (26 June 2020)

14 Clive Cookson & Richard Mile, Financial Times https://www.ft.com/content/5fd6ab18-be4a-48de-b887-8478a391dd72 (29 April 2020)

15 Tim Elwell-Sutton, Sarah Deeny & Mai Stafford, The Health Foundation, https://www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/charts-and-infographics/emerging-findings-on-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-black-and-min, (sourced June 2020)

16 Anon, The Health Foundation, https://www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/charts-and-infographics/emerging-findings-on-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-black-and-min (sourced June 2020)

17 Multiple authors, Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6915e3.htm?s_cid=mm6915e3_w (sourced June 2020)

18 Anon, New York City Health, https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/imm/covid-19-deaths-race-ethnicity-04162020-1.pdf (sourced June 2020)

19 Anon, American Sociological Association, https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2008/12/epidemiological-sociology-and-the-social-shaping-of-population-h.html (sourced June 2020)

20 Irma T Elo, Annual Review of Sociology, https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-115929 (sourced June 2020)

21 Elise Gould, Economic Policy Institute, https://www.epi.org/blog/lack-of-paid-sick-days-and-large-numbers-of-uninsured-increase-risks-of-spreading-the-coronavirus/ (sourced June 2020)

22 Anon, West Health and Gallup, https://news.gallup.com/poll/248123/westhealth-gallup-us-healthcare-cost-crisis.aspx (sourced June 2020)

23 Liz Hamel, Cailey Munana & Mollyann Brodie, Kaiser Family Foundation, https://www.kff.org/report-section/kaiser-family-foundation-la-times-survey-of-adults-with-employer-sponsored-insurance-section-2-affordability-of-health-care-and-insurance/ (sourced June 2020)

24 Sarah Kliff, The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/29/upshot/coronavirus-surprise-medical-bills.html?auth=login-email&login=email (10 March 2020)

25 Michael Posner, Forbes https://www.forbes.com/sites/michaelposner/2020/05/14/coronavirus-pandemic-reveals-our-economic-inequality/#5154abef79fe (sourced June 2020)

26 Anon, Centers for Disease Control & Prevention https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/guidance-business-response.html (sourced June 2020)

27 Anon, UN Women https://www.unwomen.org/-/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2020/policy-brief-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-women-en.pdf?la=en&vs=1406, (sourced June 2020)

This document has been prepared by MAXIS GBN and is for informational purposes only – it does not constitute advice. MAXIS GBN has made every effort to ensure that the information contained in this document has been obtained from reliable sources, but cannot guarantee accuracy or completeness. The information contained in this document may be subject to change at any time without notice. Any reliance you place on this information is therefore strictly at your own risk.

The MAXIS Global Benefits Network (“Network”) is a network of locally licensed MAXIS member insurance companies (“Members”) founded by AXA France Vie, Paris, France (AXA) and Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, New York, NY (MLIC). MAXIS GBN, registered with ORIAS under number 16000513, and with its registered office at 313, Terrasses de l’Arche – 92 727 Nanterre Cedex, France, is an insurance and reinsurance intermediary that promotes the Network. MAXIS GBN is jointly owned by affiliates of AXA and MLIC and does not issue policies or provide insurance; such activities are carried out by the Members. MAXIS GBN operates in the UK through UK establishment with its registered address at 1st Floor, The Monument Building, 11 Monument Street, London EC3R 8AF, Establishment Number BR018216 and in other European countries on a services basis. MAXIS GBN operates in the U.S. through MetLife Insurance Brokerage, Inc., with its address at 200 Park Avenue, NY, NY, 10166, a NY licensed insurance broker. MLIC is the only Member licensed to transact insurance business in NY. The other Members are not licensed or authorised to do business in NY and the policies and contracts they issue have not been approved by the NY Superintendent of Financial Services, are not protected by the NY state guaranty fund, and are not subject to all of the laws of NY. MAR00664/0720